Sonal Shah, India Abroad Person of the Year 2003, is on the move. Having tackled the poverty and disease of sub-Saharan Africa, the Asian financial crisis, and the breakdown of Bosnian society, she is steeling herself for that ugliest of beasts: Washington politics.

This month, she leaves the bipartisan Center for Global Development after serving for just under two years, and is set to join the Center for American Progress, the new, liberal think tank on the block. That job begins full-time in January. For now, the 35-year-old economist and founder of Indicorps is splitting her time between the two organisations

that dominate her daytimes: Monday through Wednesdays at CGD, Thursday and Friday at CAP.

On this particular day, she is at the office of the Center for Global Development, which overlooks Massachusetts Avenue. It sits next to the Institute for International Economics, its sister institute, and across the street from the Brookings Institution and Council on Foreign Relations, in what amounts to an impressive cluster of Washington, DC think tanks. Sonal stands in her room, dressed in black pants and blouse, and wrapped in a grey shawl. Books and files lie scattered on the floor or in stacks on chairs. Boxes sit, opened, holding mementoes from her previous job at the Treasury Department, where she worked for several years.

She joined the CGD when it was formed, and as Director of Operations and Programs, has been responsible for most of the Center's hiring, and for managing its policy and advocacy programmes. The organisation conducts research on globalisation and its impact on poor people throughout the world, and promotes policies it feels contribute to equitable growth.

Sonal was brought in from the Treasury, where in her six years she dealt with one regional crisis after another. In 1996, in the immediate aftermath of the war in Bosnia, she served as a Treasury Attaché in Sarajevo. There, she worked with Secretary of the Treasury Robert Rubin and others to restore the local banking system, establish a new currency,and help balance the demands of various ethnic groups. Later, she became a regular fixture in Southeast Asia, helping bring the financial crisis under control even as riots swept around her. When she left the Treasury, it was as the Director of the Office of African Nations, helping negotiate debt and AIDS for sub-Saharan nations.

It all sounds quite dramatic -- visions of American economists parachuting into hyper-inflated territory -- but of course, quite often, violence was close at hand, a result of local economic policy run amok. Nonetheless, you get the impression that, for the understated Sonal, drama is built into the job description.

It all sounds quite dramatic -- visions of American economists parachuting into hyper-inflated territory -- but of course, quite often, violence was close at hand, a result of local economic policy run amok. Nonetheless, you get the impression that, for the understated Sonal, drama is built into the job description.

"You'd hear a lot of automatic gunfire," she says of her time in Bosnia, "but it wasn't major."

The phone rings. It's a former colleague from the Treasury.

"You were back in Sarajevo?" says Sonal, perking up, "Wow, how's it looking?"

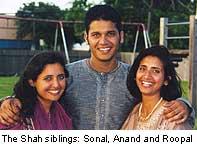

They chat for several minutes, mostly about the elections in Bosnia. There's a no-frills quality to Sonal -- not a smidgen of makeup, for instance -- and her office is a relatively spare room that looks out onto the passing traffic of Massachusetts Avenue. Among the few personal touches is a framed photo of Sonal and her siblings, Anand and Roopal,

taken after a wedding in Houston. All three beam into the camera with very large, very hazel eyes.

Two years after Sonal was born, her father Ramesh moved from Gujarat to New York in 1970, where he worked odd jobs, mostly as a boiler inspector in apartment complexes, chemical plants, and laundromats. Sonal, Roopal, and their mother Kokila joined him in 1972. Ramesh worked for a couple years as an engineer before shifting the family to Houston. There, the family became very involved in the Gujarati community, helping establish the Gujarati Samaj and annual religious events like the Navratri celebrations. It was, says Ramesh, the family's way of recreating India.

"The one basic part which affected all of our lives was Swami Vivekananda's readings," says Ramesh. "When I came here, it was tough, so that reading helped us a lot. That made our love for India -- doing something for India -- stronger. Even if we didn't go [to India], it was there."

The family was influenced by Indian social reformer Pandurang Athavale who founded the Swadhyaya movement in the 1950s. Athavale was a deeply spiritual man who would quote from the Gita as well as Kant and Marx. He frequently visited villages wracked by alcoholism or crime, giving discourses and encouraging volunteers to build homes and teach locals advanced farming and fishing techniques. He died this October, on Diwali, but not before his movement had brought several million people under the tent, including the Shahs.

Sonal and her siblings all connected to Athavale's teachings, particularly to the notion that one can transform oneself through social work.

The first impulses of what would later turn into Indicorps came in 1988. That summer, after her sophomore year at the University of Chicago, Sonal, her mother, and siblings bought three-month rail passes and participated in rural development projects around India. They stayed in Uttar Pradesh, Kolkata and the tribal region that is now called

Jharkhand, before traveling south to Madras [now Chennai], Pondicherry, Kanyakumari, and Dharwad, in Karnataka. Along the way, they formed friendships with local activists, including some who had left America or urban India in order to work in the villages. The experience left a major impact on the 20-year-old Sonal who eventually wrote her senior

economics thesis on the development work she'd observed in Uttar Pradesh.

In 1990, Sonal graduated and spent a year wandering through rural India, Kenya, Uganda and Mozambique. She would land up in one small town after another, looking for work and seeking out shelter wherever possible -- the home of some distant acquaintance or someone she'd just met -- even occasionally crashing out at a local train station.

"My relatives in India thought I was a nutcase," she recalls with a laugh, "but my parents were supportive."

Sonal received a Masters degree at Duke before returning to work in Houston, for Anderson Consulting. During this period, she started taking a leadership role involving other young Indian-Americans in social projects. One of her favourites was called Impressions, a scholarship initiative she directed that drew solely upon Indian-American youth efforts in the Houston area.

However, she increasingly realised there was a need for something that took Indian-Americans to India. She and Roopal were admirers of Teach for America -- the Clinton-era initiative that took college graduates to inner-city schools -- and came up with Teach for India. The programme never took off. The Shahs had trouble finding funding and they came to the conclusion it would be beset by problems, not least of which was the language barrier that Indian-Americans would confront in rural Indian schools. However, this didn't deter Sonal for long, and for the most part she thinks all challenges work out for the best.

"If one programme didn't work well, it led to an opportunity to do another programme," she says. "The setbacks we faced only opened other doors for us. But, then again, I don't really have a negative outlook on anything."

Then, in 1998, her brother Anand took a year off from Harvard to study at a philosophical school run by Athavale's followers in Thane, outside Mumbai. Anand was one of 10 students from America who participated in the programme. He realized along the way that there were many other Indian-Americans his age who were interested in spending structured time in India, working with organisations that had clearly defined agendas.

His ideas excited Sonal and Roopal. This seemed to be an inspired, workable plan, along the lines of the Peace Corps. With his sisters' financial help, Anand stayed on in India, personally researching dozens of non-profits and NGOs, winnowing out the less relevant or productive ones. Meanwhile, Sonal and Roopal sought out funding in the US, structured a programme, and drafted a 12-page application. Sonal's contacts throughout the development sector were crucial -- they helped the trio create a cutting-edge programme and brought in the manpower that often eludes well-intentioned start-ups.

Sixty people competed for the first 10 Indicorps fellowships. Anand returned to the States in time to help with some of the on-site interviews that the siblings conducted all over the country.

In May of 2002, the first batch of Fellows had been selected. By September, they were on the ground in India, and Indicorps was underway.

Part II: Indicorps: The saga continues...

ALSO SEE

Images: India Abroad Person Of The Year

A community honours one of its own

Sonal Shah is the India Abroad Person of the Year 2003

India Abroad Person of the Year 2003

Title photograph: Paresh Gandhi

Photograph of the Shah siblings: Courtesy the Shah family

Image: Uttam Ghosh