For 20 years, Japanese architect Takeo Kamiya visited India like any ordinary tourist. He travelled the country, unnoticed by his Indian counterparts, meticulously photographing and documenting monuments and buildings. Then, three years ago, an Indian architect visiting Japan accidentally stumbled on a chunky tome published in Japanese. He decided to uncover its secrets for his people back home.

Until a few months ago Gerard da Cunha was a respected Indian architect with a successful practice in Goa. But recent events have seen him scale new heights among his fraternity. His efforts over the past three years have revealed to the English-literate world a treasure trove of pictorial information on Indian architecture.

This is more than a tale of two architects and a book. It is a parable for Indian architects to seek their muse in their own rich tradition.

"Traditionally, Japanese students go to Europe or America for their research," Kamiya told rediff.com in halting English. "But since ancient times, the Japanese have felt a lot of respect for India, maybe because Japan is a Buddhist country. Twenty-seven years ago, I could not get any information about Indian architecture. I had not studied much Indian history and I did not know anything about Indian culture."

Kamiya, 57, first came to India in 1976 by bus via the Asia Highway from London to Kathmandu. The currency exchange rate at the time (35 Japanese yen to a rupee) mandated a tight budget. Communication was also a hurdle, as he spoke only snatches of English.

"Of course, I could also not speak any Indian language," he laughs. "But for young people, it does not matter."

Another reason Kamiya was drawn to India was Mahatma Gandhi's philosophy. "I visited India in the spirit of Gandhi," says the silver-haired architect.

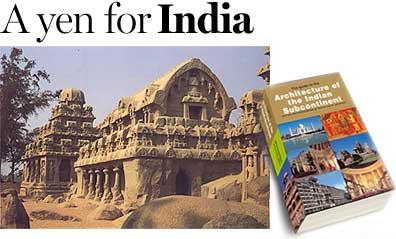

Kamiya divided the map of the Indian subcontinent into a grid of several tiny squares. He marked out the buildings he wanted to study in each square and accordingly planned his travels. He painstakingly photographed and documented about 560 monuments in India and Bangladesh, leaving out the northeast as it was out of bounds for foreign visitors.

He classified the monuments into three categories based on architectural principles: Sculptural (where entire buildings, such as stone-cut medieval Indian temples, resemble sculptures often with intricate carvings); Membranous (where the emphasis is on enclosure of interior space, as in Islamic and Middle-Eastern buildings) and Framework (where interior and exterior space are continuous without clear distinction, as found in Japanese wooden buildings).

Some of Kamiya's inferences can be startling. Having studied the monuments with an architect's disaffection, he proves by means of a cross-sectional sketch that some Indian temples were, apart from their physical beauty, not very functional. Or that the Taj Mahal's dome is its biggest architectural drawback. "It is dead space," he said, eliciting a shocked murmur from the audience at a lecture in Mumbai.

It took him 12 trips for a few weeks every year before he had all the material he needed to write The Guide To The Architecture Of The Indian Subcontinent.

By 1996, the book had been published by Toto Shuppan, Tokyo, and Kamiya had moved on to other things, like teaching at Tokyo University.

Four years later, da Cunha arrived in Japan.

"I had been to Tokyo for a conference and a photographer friend gifted me this book," recalls da Cunha, who has worked closely with the legendary architect Laurie Baker and authored the book Houses Of Goa. "It was comprehensive and showcased Indian architecture in its entirety. Unfortunately, it was in Japanese."

Thumbing through the book, he saw it was an account like nothing published in India -- with 300 maps, structural line drawings and illustrations, and 1,800 colour photographs, besides travel information. It was the book of his dreams, and a Japanese had written it.

Back in India, he wrote to the publishers who were initially reluctant to grant the rights for an English translation. They grumbled about the quality of printing in India and said the cost of reproducing the plates alone would amount to about Rs 7,000,000.

Undaunted, da Cunha wrote letters to the Japanese government and to various Indian ministry officials. The Jindal Art Foundation, run by art patron Sangita Jindal, stepped in to fund his effort. The Guide To The Architecture Of The Indian Subcontinent was eventually translated into English by Geetha Parmeshwaran in Bangalore, edited by architect Annabel Lopez in New Delhi and printed at Hyderabad.

"The book appeals to three sets of people: architects, travel professionals and heritage people," says da Cunha. "It is an ideal textbook for students of architecture."

"This book should go to every school," eminent architect V Balkrishna Doshi commented before releasing the book in Mumbai. "It makes you think: if the people who built these monuments were alive, what would they build?"

He felt that it was vital for "information-based tourism" and hoped it would help lesser-known monuments get a new life.

"Every small village has its heritage sites -- its tanks, its banyan trees, its temples -- but we never look at them closely," says Doshi, a 1976 Padma Shri recipient who has worked under such legends as Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn. "Visiting monuments is essential for documentation. If students use this book and go to those villages, they will understand our heritage."

Da Cunha feels the book is an asset to travel professionals because landscapes don't appeal any more. "You have beautiful beaches not just in Goa but in Seychelles and Mauritius as well," he says. "The only thing we have in India besides the geography is the most diverse architecture in the world."

More important, he says, is the book is the first comprehensive listing of Indian architecture, which makes it an indispensable handbook for heritage tourism. "The listing will be taken seriously," da Cunha says. "INTACH [the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage] was happy with it."

He feels the book is a steal at Rs 1,200. "But I see more foreign tourists buying it. Indians don't buy a lot of books."

Kamiya, who has also authored books on Hindu and Islamic architecture, is studying the history of Indian architecture for his next work. Meanwhile, he is concerned for the future of the buildings he has photographed.

"Only the buildings maintained by the Archaeological Survey of India are in good condition," he says. "In the temples of Himachal Pradesh, they have started to paint the [ancient] wood carvings in red, blue, black and yellow. It looks comical and makes me very sad."

Click here for glimpses from The Guide To The Architecture Of The Indian Subcontinent.

Image: Uttam Ghosh

To order The Guide To The Architecture Of The Indian Subcontinent, write to archauto@sancharnet.in. More information is available at https://www.indoarch.org.

© 2025

© 2025