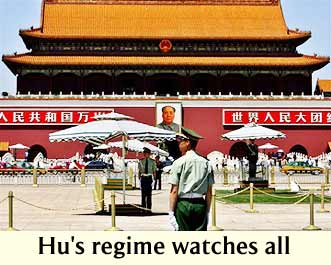

Sixteen years since the bloody crackdown on Tiananmen Square, China's grip on dissent has tightened under the leadership of President Hu Jintao, disappointing those who hoped he might represent a more tolerant leadership.

From religion to the media, political activism to the Internet, Hu's regime watches all -- and silences all that challenge the Communist Party's authority.

Members of non-sanctioned churches risk detention, potentially incendiary chat rooms are shut down, newspapers are kept under a short rein and employees of foreign news organizations have been arrested and accused of spying. Last month, an international conference on democracy was canceled.

When Hu came to power in 2002, many speculated that the new generation he represented would re-examine the crackdown on the Tiananmen Square pro-democracy protests -- which mark their 16th anniversary Saturday. But he has refused appeals to do so.

China: The passing of the baton

"Hu Jintao is by inclination a more authoritarian figure than (former President) Jiang Zemin," said Steve Tsang, a Chinese politics specialist at Britain's Oxford University.

"He takes a harder line against dissent than Jiang. He's much more decisive. He can see what needs to be done to maintain the regime's position and he's willing to do it."

This week, Beijing accused a detained Hong Kong-based reporter of spying for "a foreign intelligence agency."

Ching Cheong, chief China correspondent for Singapore's The Straits Times newspaper, was detained last month. His wife said he was trying to obtain a manuscript of a book on the late Communist Party leader Zhao Ziyang, who was purged after sympathizing with the protesters in 1989.

The protests are a still sensitive for China's rulers, which have deemed them a counter-revolutionary riot. Hundreds, if not thousands, were killed when the government sent tanks and troops into Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989, to crush a month-long occupation by protesters.

Each year, authorities try to prevent public memorials by confining dissidents to their homes or taking them away from the capital as the anniversary approaches. Security officers patrol the square and quickly arrest anyone who unfurls a banner or shouts remembrance.

"Even if I don't see police in front of the house, my phones are tapped. I am never at ease," said Ding Zilin, whose son was killed in the bloodshed. She is a co-founder of the Tiananmen Mothers, a group that represents families of those who died.

"The repression has become worse since Hu Jintao took power," she said.

The Tiananmen Mothers released an open letter to Hu last week, appealing to the government to reassess the crackdown, which Chinese leaders have defended as necessary for what they say is the country's stunning economic success.

"We've done this for 10 years and we've never gotten an answer," Ding said.

Hu's government has presented itself as one dedicated to improving the lot of the people, especially the rural poor. There is also a strong sense of corporate efficiency.

Those who do not measure up -- like former Health Minister Zhang Wenkang and Hong Kong leader Tung Chee-hwa -- are fired.

Hu has also shown little patience for public dissatisfaction, said David Zweig, director of the Hong Kong-based Center on China's Transnational Relations.

"He certainly has not shown himself to be the liberal that people thought he would be," Zweig said. "He has responded quite forcefully to challenges to the party's authority. They are very nervous about social unrest. They want to hold on tight to their power."

Aside from favoring one-party rule, Hu's own agenda is unclear.

From Roof of the World to Top of the Party

"The difference between Jiang and Hu is that Hu is far more popular than Jiang among the Chinese public," said Cheng Li, a professor of political science at Hamilton College in New York.

"Hu has more political capital. The message is a mixed one. Hu wants to promote political reforms, as he states, but these political reforms should not be out of control."

Civil uprisings in its central Asian neighbors -- Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Georgia -- have sparked unease in Beijing that another 1989 protest could happen again.

"They have stirred up the worries of the Chinese leadership so they feel justified taking a hard line," said Lai Hongyi, a research fellow at the East Asian Institute of the National University of Singapore.

"In recent number of years, there have been a drastic increase in protests," Lai said. "If they still allow the liberals to speak out, that could instigate more incidents, it would encourage a bigger movement and destabilize the government and the party's control."

Design Uday Kuckian/(AP Photo/Elizabeth Dalziel)

© 2025

© 2025